What's The Difference Between Language Learning And Acquisition? (And Why One Is Better)

When people speak about foreign language fluency, they often describe it as “language learning”. Then, when you get a little more into it and you start reading articles that go a little more in-depth, you’ll start hearing the term “language acquisition”. Why this fancy term? You might ask. Isn’t it the same?

Well, no.

When speaking about reaching fluency in a foreign language, there’s a distinction between language learning and language acquisition.

So what’s the difference?

Check out “The Power of Reading” by Stephen Krashen - a book that suggests that language acquisition through reading is the most natural (and superior) way to acquire languages. (Link to amazon)

Learning a language is analyzing and exploring its intimate details until you know information about it. Language acquisition, or to acquire something is coming to own something. Acquiring a language means coming to know it intuitively as you did with your mother tongue.

When it comes to speaking foreign languages, learning languages would entail analyzing the language, cutting it up into pieces, and trying to figure it out. What are the grammar rules that make the words act like that? And so on. This type of language study would entail a lot of memorization of information. You’ll gain knowledge about grammar, pronunciation rules and so on.

If we speak about acquiring a language, you’re not really dissecting or analyzing the language in order to understand it. You’re just getting used to it. You’ll know if something is correct or not just from hearing or seeing the sentence. It’ll just sound wrong, and you’ll immediately change it to what it’s supposed to be. But you wouldn’t be able to explain why.

In academia, language acquisition is seen as the way children come to speak their first language. Since they don’t yet have a first language to use as a tool to analyze the language, they’ll need to learn it instinctively and intuitively rather than analytically. Then as the children get older and start attending foreign language classes in school, they start “learning” a second language, using their first language as a facilitator.

But while acquiring their first language was intuitive and almost automatic, studying their second language, doing grammar drills, exercises, and memorizing rules, is forced and tedious. While the children end up learning a lot about languages, they often have a hard time reaching fluency.

The Brain Deals Differently With Acquiring And Learning

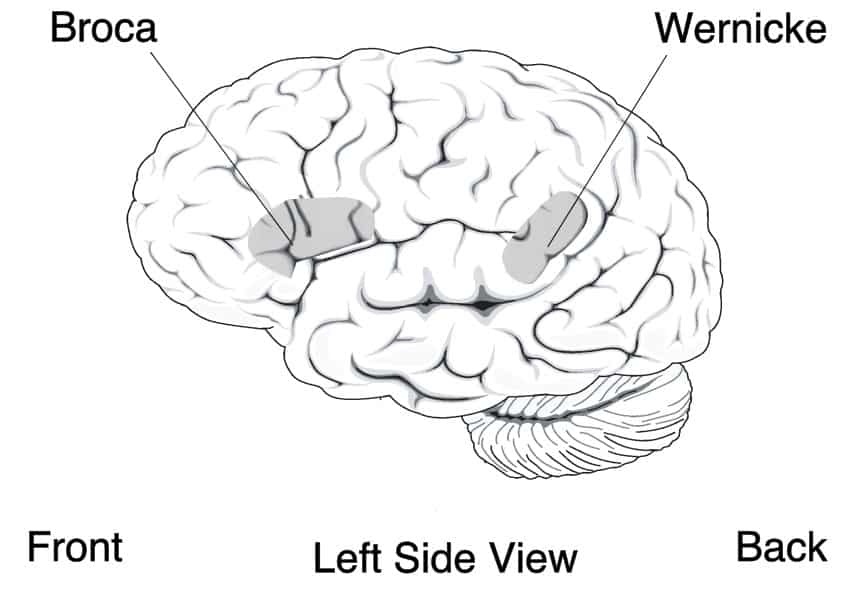

The difference between language learning and language acquisition is not just theory. It’s something that you can clearly see in the brain when neurologists look at it with various brain imaging techniques, while at the same time making the individual being scanned either perform learning or acquisition tasks. When these tests are performed, it’s clear that two different areas in the brain are used for the two different language techniques.

One is Broca’s area, which is active while the individual is performing language acquisition tasks, the other is Wernicke’s area, which is active for analytic tasks more in the lines with language learning.

How To Use Language Acquisition To Reach Fluency

So should you focus on language learning or language acquisition if you want to be fluent in a new foreign language?

For me, there’s no doubt that language acquisition is the way to go.

“Language learning” will be a benefit if you want to figure out what makes a language tick. What are the underlying mechanisms that make it function the way it does and so on?

This is interesting from a linguistic point of view, and you’ll learn a lot of interesting things about how we communicate… But it won’t help you speak the language.

To actually become a fluent speaker of another language, you need to “acquire it”.

Infants do this by listening for a very long time. Your parents and relatives spoke to you and all around you for months and years before you uttered your first word. And when you did, chances are that you said it incorrectly and were corrected. (Again and again..)

A child gradually develops his or her first language from listening, trying, and failing over and over again, until the words and phrases start to sound right. Because of listening so much, we know exactly how our mother tongue should sound, and it immediately stands out when something is wrong.

And because of being corrected over and over again, we know exactly how to say things the right way. We wouldn’t be able to explain the grammatical rules, but we know what’s right or wrong.

Now, how can we use this approach to acquire languages as adults?

Some people say that people lose their capacity to acquire languages when they grow up. This is false. But can you use exactly the same method as you did for acquiring your native language?

Well, you could.. But it wouldn’t be practical.

And to be honest, it’s not that efficient either. The fact of the matter is, that you have an advantage in language acquisition over an infant.

While the child has no point of reference, you have English. The child is just getting started at life, but you’ve got experience and intelligence. The child is limited to the input he or she gets from parents, relatives, and caretakers, whereas you can pick any kind of foreign language material you like, and focus on what you want and need to learn first.

So what I advise you to do, is to consume your target language. Listen a lot. But since you have the advantage of knowing how to read, go ahead and do that too. And read a lot.

I strongly recommend LingQ as a tool for learning languages through reading.

(Here’s an article I wrote about LingQ)

An infant will listen to speakers of his or her native language for many months before saying the first word. You can skip ahead. A little and repeat what you’re hearing. Do so again and again and again.

(For this, I strongly recommend the language learning system Glossika, which I’ve previously written about).

And while children acquiring their first language have no points of reference, you have English. So compare the two languages. Figure out what the foreign language means. You might do this by looking up words, or even better, reading the English version of a book in parallel with the Foreign language version.

And then there’s communication. As a language self-student, the task of beginning to speak and write in your target language can be a little difficult. How do you get started with speaking and who do you speak to?

Getting a tutor, and laying out a strict plan, might be an approach. But your tutor needs to be on the same wave length as you. You should rely on conversation. No grammar explanation or analysis.

But while communication is one of the single most important parts of language acquisition for infants, I think that it can be postponed a little for adults.

Children rely very strongly on the input of adults who speak to them. You can listen to the radio, audio lessons or watch TV. And while you’re going to need corrections as children do, you have the advantage of being able to work at the language in a much more structured way.

You can compare the foreign language to English. You can record yourself and listen to your pronunciation. And you can learn a lot more from input than children can because you’re handpicking what to read and listen to, whereas children only consume the kind of language that’s available to them completely at random.

Conversation is important and should not be neglected at all. But it can be postponed to a later time in the language acquisition process.

Acquire A Language, Don’t Learn It

While research in the way we come to speak languages has proved time and again that to speak a language you need to rely on language acquisition rather than language learning, the latter is still the most prevalent in most educational institutions.

Language students are asked to memorize conjuration tables and grammar rules. They study to pass tests, do drills and exercises rather than actually communicate in the language. And the result is a low success rate when it comes to second language proficiency. Very few students end up actually speaking a foreign language, and those who do, don’t do it very well.

That’s a shame!

Language acquisition is both much more effective, but also much easier. Students don’t have to memorize dry facts, dissect sentences and analyze their parts, and learn about complicated grammar structures.

To speak a language, they’ve got to start using it.

So if you’re a language student, I encourage you to start taking charge of your own fluency. Do what will actually get you to speak the language, and let grammar drills and exercises take the back seat. You’ll find that the experience is much more pleasurable and the outcome much better!